The Things My Ears Enjoyed

A sonic reconnection to my granddaddy.

My granddaddy once said, “In memory lie the seeds of improvisation; in technique, the means by which to cultivate the memory, nourished by both tradition, in the form of myths, and by whatever science is available, even if it is called religion or magic”.

They say he was a curious child who would roam around his hometown of Buttermilk Bottom in Atlanta, Georgia, BB gun and German shepherd in tow. A boy who traversed unpaved roads through Beaver Slide, collecting pecan shells on the way to school.

They say.

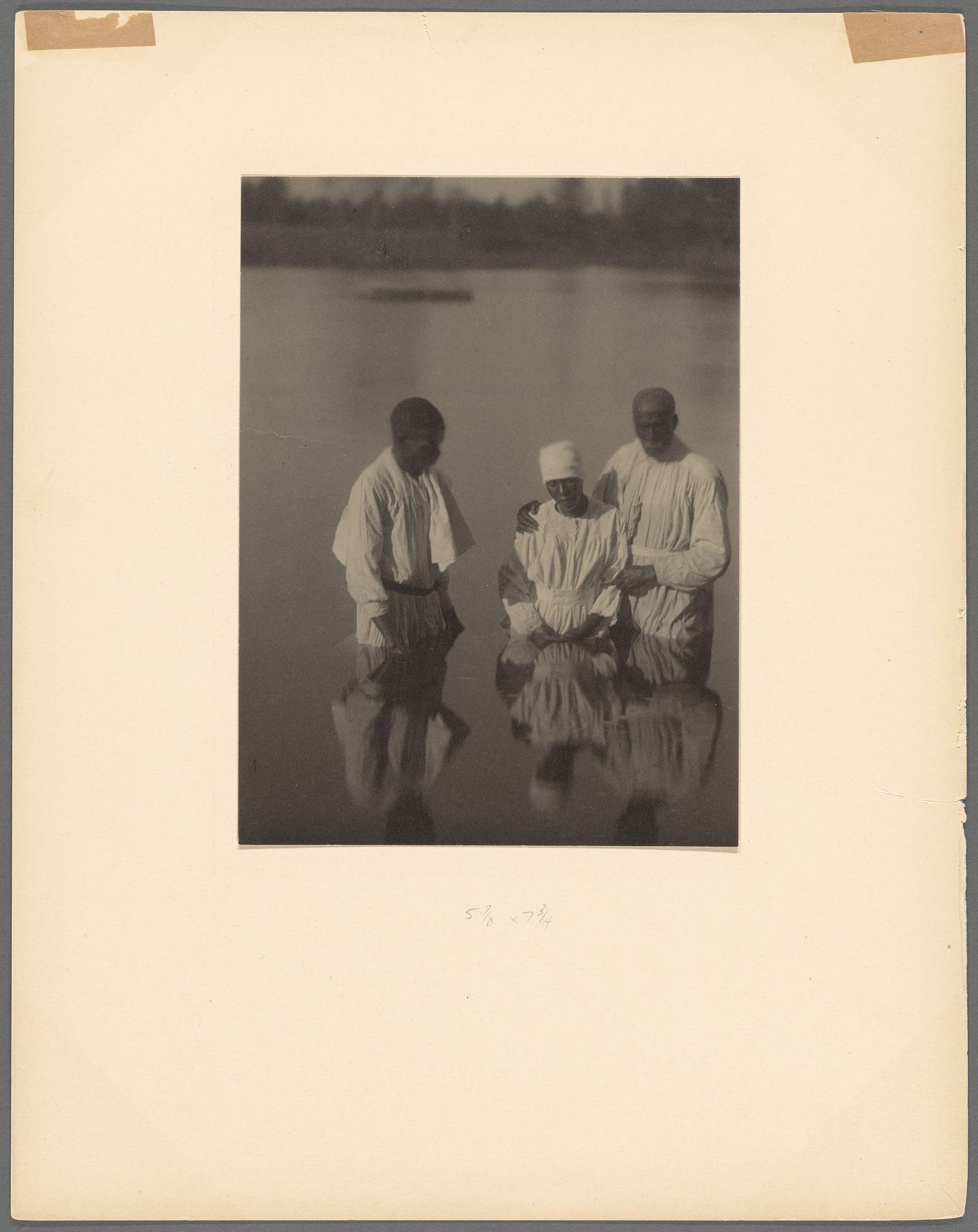

They say his granddaddy was a healer who cared for his community through his relationship with bark and plants and roots and twigs. From the Congo, he arrived to the eastern shores of Turtle Island on the Wanderer, a slaveship that docked off the coast of Georgia at Jekyll Island in November 1858. At any given moment, my great-great granddaddy’s stovetops were busy conjuring up herbal remedies, keeping alive traditions passed down from his granddaddy, and all those before him.

A teen, he lived in many a place, they say. Like, in the woods, and with his uncle in rural Georgia. His Sunday mornings were filled with hymns sang at Flipper Temple A.M.E. Church.

Survivor of the Great Depression and Jim Crow. Member of the 1st Cavalry Army Band during the Korean War. Clark Atlanta and Howard-educated. Ethnomusicologist. Friend and confidante to Amiri Baraka and Coltrane. A man of idea and improvisation and imagination, they say.

Third-generation Gullah Geechee.

He’d find his way to New York City by 31.

Through his music, my granddaddy was a bridge to his past. And to my daddy’s past. And to mine. To ancestral realms whose doors would welcome him later in my childhood. Most of his songs––or, sonic odes to bygone times––dubbed “avant-garde”. As to say, these sounds are so foreign, they cannot exist within the confines of my western framework-trained ears. As to say, I cannot understand because these sounds have not yet been colonized.

By the time I was born, he was already sick. And by the time I was a school-aged child, he had embarked on his journey back home. Yet, I remained steadfast in my pride, telling any who would listen that yes, I was, I am, Marion’s granddaughter.

While I knew the importance of his legacy as a concept, the majority of my life bore frustration whenever listening to his albums. I was mad at myself for my inability to process the very work my kinfolk had poured so much of himself into. At first, it was pure cacophony. Or, depending on the record, all I heard were water drops and clicks and pops. Whistles and echoes and Nature conversing amongst Herself.

And then one day, my granddaddy called unto me to dive into his memory. See what I could find. What I could listen to. There were messages waiting for me to uncover. Questions and answers about my heritage, about what it means to be a fifth-generation (diasporic) descendant of the Gullah Geechee corridor.

Beauty. Majesty. Wonder. Alchemy.

Why Not? (1968) resets my nervous system, while Vista (1975) makes my heart ache. Three For Shepp (1967) is gangsta, and Porto Novo (1967) is afro-futurist. Sweet Earth Flying (1974) is a precious honeysuckle kiss. Geechee Recollections (1973)––whose album cover was photographed by Mima, my Afro-Native [Nanticoke-Lenni Lenape, Comanche, and Powhatan-descent] grandmother––is an ancestral case study and vital moment in my daddy’s origin story. Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (1971) is a invitation to be still and sit beside my granddaddy as he listens to all things, big and small, on a hot summer day.

Both Geechee Recollections and Afternoon of a Georgia Faun have been instrumental in the active re-membering of parts of my Self I didn’t know I had forgotten. My matrilineal Caribbean-Taíno-Arawakan heritage and paternal grandmother’s Afro-Native lineages are deeply rooted in me. But, connections to parts of my paternal granddaddy’s heritage have been lost. By engaging with his music, he and I create new memories. Memories that pull me so close, I feel the faintness of a Southern breeze graze my cheek as sweat collects at the brow.

I’ve learned that, similar to the Caribbean communities and Turtle Island Afro-Native ancestors whose legacies I carry, for Gullah Geechee, everything is Spirit. As an Olorisha Yemayá––initiated priestess of Yemayá within the Regla de Lucumí faith––a key pillar of my faith is rooted in honoring the ancestors. Speaking their names. Building them altars. Leaving them offerings of food and flowers, coffee and cigarettes. In all aspects of my being, everything I do is for and of Spirit.

From the melodic to the experimental, Marion Brown is a musical study of tenderness. Through the progression of each note uttered by his saxophone, I feel the warmth of his embrace. Hearing his breath between notes and his fingers clicking on the keys, I’m reminded of his presence. He is very much alive.

Reconnecting, sonically, with my granddaddy has been a reawakening of, Spirit. His, which is given strength every time his name is spoken, or when a record is played, or, when I think about him and am moved to tears. And mine; the part of me that has only travelled to Georgia once, but was rendered speechless by contemplating the beauty of sunsets in the land my ancestors once toiled.

I play a song, and think of Marion, the innovator. I look at videos of live performances, and think of Marion, the artist. I look at images of him with my daddy and Mima and see Marion, the flawed. I see him immortalized on the college campuses of New England that he both attended and taught at, and see Marion, the forever-student.

I think of Marion, and I think of many of history’s unsung Black artists who gave more than he got. I try not to think about the last years of his life, marked by illness and a partial leg amputation. Or about the sadness I felt visiting him at nursing homes, watching him deteriorate along with other elders unable to (for varying reasons) spend the rest of their days surrounded by family.

More often, whenever his memory is activated, I think about Marion, the boy. Who would lose his mother, my great-grandmama Marie, while he was still young. I think about the music they would dance to together, and of his favorite family meal. I think about the soil that once buried itself deep beneath his nails as he played in the dirt, and hardened mud on elbows and kneecaps. I think about him seeking the comfort of relatives during a thunderstorm, and the lullabies that once rocked him to sleep. What he thought while watching his granddaddy conjure up ancient medicines, and how he made sense of the world with those big eyes. I wonder what kind of student he was in class, and which subject he struggled with the most.

Whether music or academia, Marion’s artistry was the site that allowed him to wrestle with, deconstruct, and reimagine identity. A Black man from the South first, my granddaddy remained committed to using his gifts as pathways to document his experiences, and those of his parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles, ensuring the soul of his people would forever be immortalized.

The story of my reconnection to my granddaddy and our heritage is a call for all of us to step into the role of our family’s memory keepers, and an opportunity to investigate the parts of our being that may feel farthest away. As Black, Brown, Indigenous peoples of any lands, we must do the spiritual-emotional-psychological work of realigning ourselves to all we encompass. Ask your relatives questions, and scan photographs and important documents. Build oral histories, beginning with your elders. Collect family recipes in tangible form, so they can be kept for generations. The ability to preserve is at our fingertips.

To the keepers of history | Remain curious about all that makes you who you are. Do so in and for love: of your Self, and for all those who were, so you could be.